In today’s noisy, scrappy conversation about food, a pitch-perfect note once in a while bubbles to the top. Bee Wilson, a food historian and author, recently brought us one of those sparkling notes in her review of William Sitwell’s new book, A History of Food in 100 Recipes. Wilson writes reviews in The New Yorker and sometimes her own books, such as Consider The Fork, published by Basic Books in 2012.

While offering her thoughts on Sitwell’s attempt to extract historical narratives from ancient recipes, Wilson slips in a short riff about storytelling and the idea that a recipe is a story. As a fictional story, a recipe hints at the possibility of a resolution. A recipe invites a reader to follow a narrative, a set of instructions, with ingredients that have their own character traits along a story arc that evokes both drama and denouement. The setting of the story belies the writer’s own attitude, place, and culture. Recipes can be stories within stories.

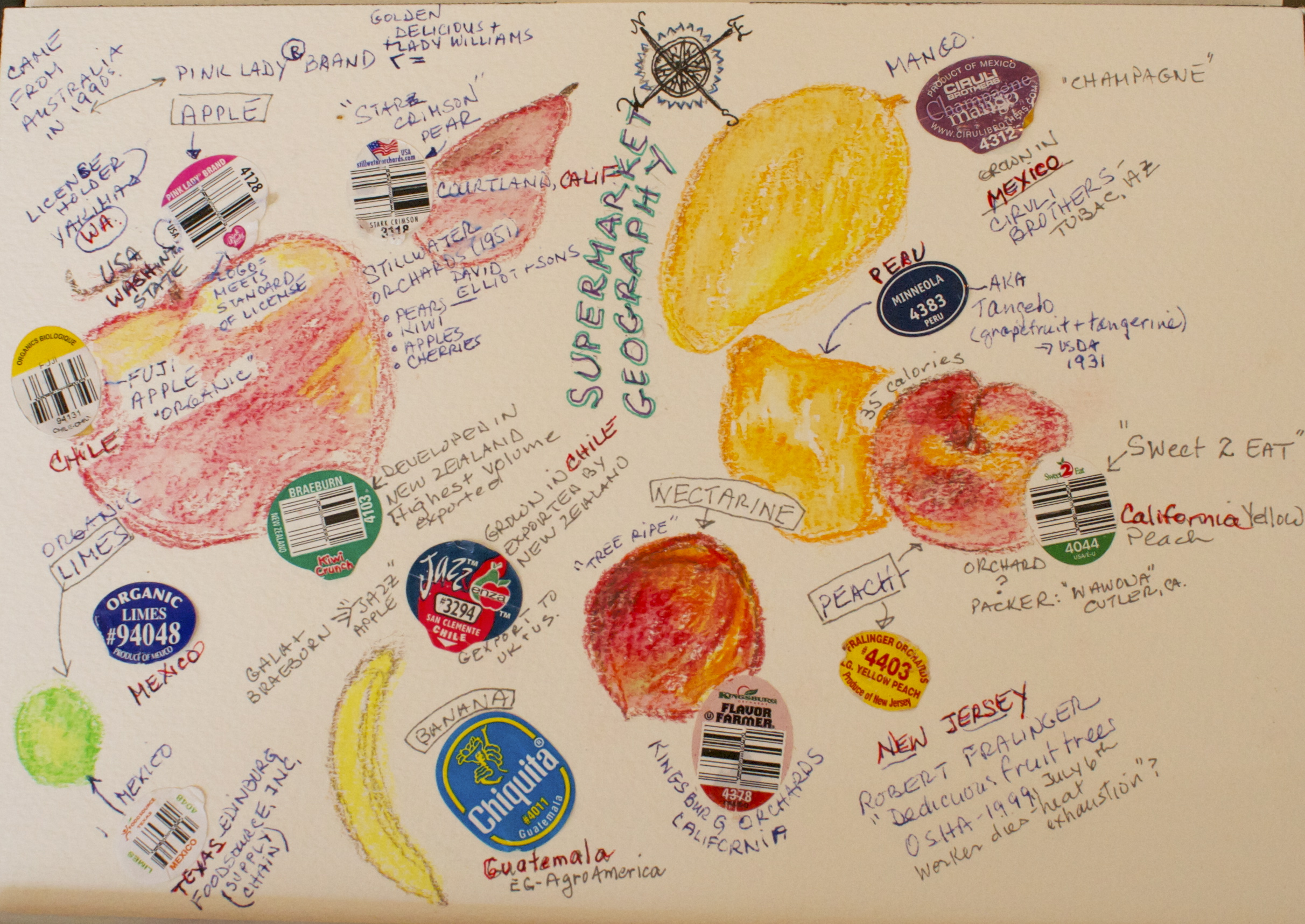

But so can other readable texts, such as those pesky stickers that adhere to the fruit we buy from grocery stores. For a week this summer, I began peeling off PLU stickers from the fruit that I purchased from two grocery stores. PLU stands for “Price-Look Up” and are codes that tell us where our fruit comes from and how it was produced. The codes first appeared in 1990 and are now sometimes accompanied with bar codes. They lubricate the trade of produce around the world.

The codes are easy to decipher: Four digits indicate the probable use of pesticides, five digits beginning with a eight mean that genetically modified organisms were used during production, and five digits beginning with an nine mean that the fruit was produced using organic methods.

I randomly chose the fruit, not intending to buy local or organic or non-organic, but buying what I needed at the time and looked fresh. The stories of these fruits emerged and included the following: None of the fruits were genetically modified. Out of twelve fruits, only two were organically produced, which was surprising since at least half of the fruit came from a Whole Foods Market in Maine. The rest were non-organic and came from California, Mexico, Guatemala, New Jersey, New Zealand, Chile, Washington state, and Peru. Here is my PLU Map.

By looking up the codes, you can sometimes find the names of the growers, packers, family names and histories. Some of the stories that surfaced were personal. One grower had received an OSHA violation for a worker who died of heatstroke while harvesting fruit. Reading the details of the worker’s death, I felt uncomfortable, sensing that these details were not for public consumption. I wonder how this individual’s family would react to the knowledge that someone who casually bit into a nectarine shared the intimate details of his demise. I was left wondering if the grower was somehow responsible for the death, or was the worker already in poor health and in spite of being advised not to come to work, came anyway on one of the hottest days that year in California.

So even PLU stickers reveal stories, like recipes, complete with drama, tension, and resolution. Someday those stickers will be edible and we’ll eat the words of producers, food scientists, and processors.

Stickers, recipes and Bee Wilson’s fine story telling are contributing to my current interest in storytelling. How many ways can you tell a story? What makes a good story? What do you think?