While the world watches Syria cross red lines, Syrians contend with breadlines. Hardly a grenade passes through rebel or military hands without making an impact upon the country’s food supply. Collateral damage inflicted on crops and animals rarely reaches consumers of news about the Syrian crisis.

Throughout history, governments have recognized the link between war, food, and national security. The Romans noticed the connection when they sought food sources throughout their empire; the French saw a revolution ignite over bread prices, and in 1812 Napoleon observed the starvation of his army in Moscow, leading to his famous remark that “an army marches on its stomach.”

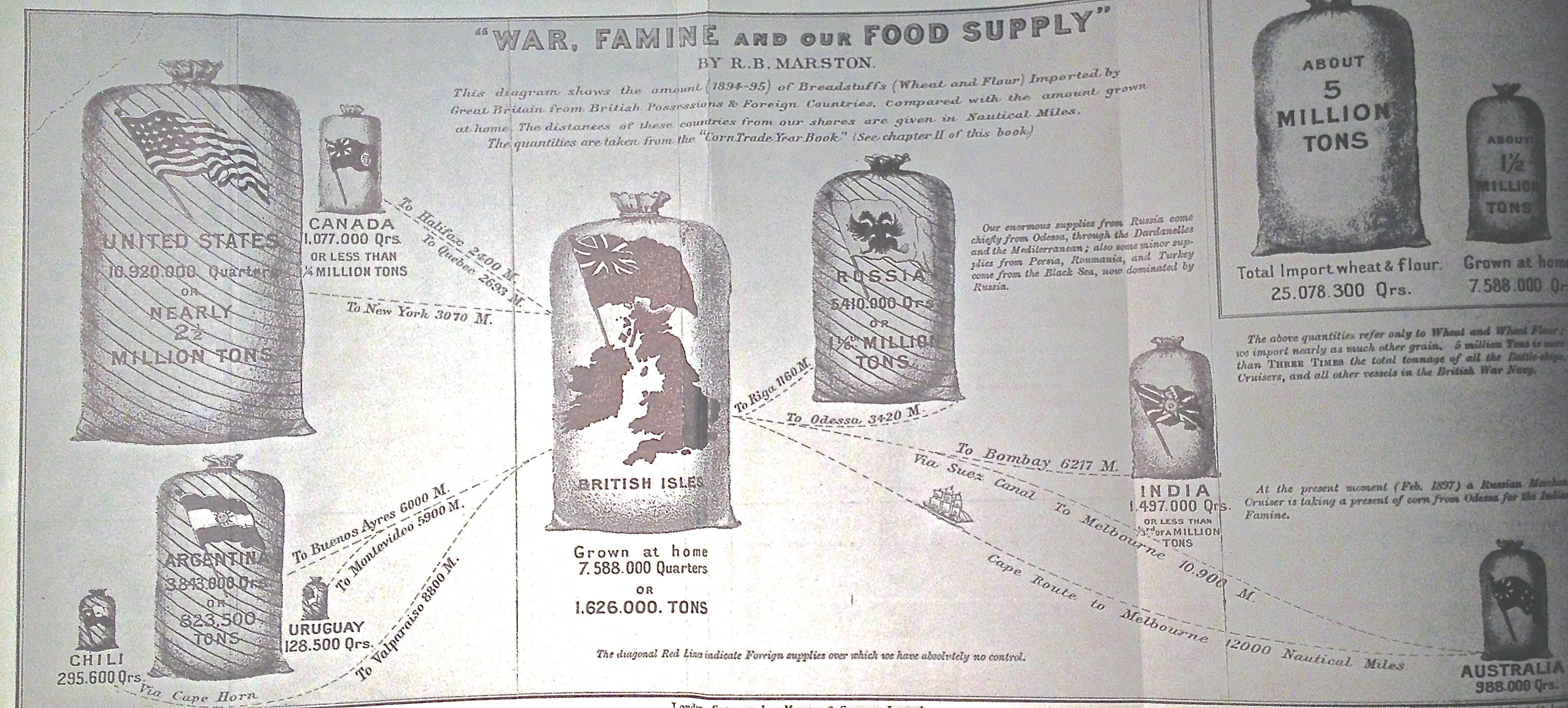

So in 1897, when Robert Bright Marston drew upon Napoleon’s observation to argue for greater food security for Britain, he was well aware of the link between a nation’s ability to feed itself and national security. In particular, he was worried about Britain’s reliance on Russia and the U.S. for wheat and corn. Marston envisioned the construction of grain storage buildings that would enable England to live for three months if a war cut the country off from Russian and American grain. You can see from his illustration how he saw the relationships between grain suppliers and the British grain supplies.

Marston’s View of British Grain Dependence

Marston, a British writer known for books about fly fishing, wrote War, Famine, and Our Food Supply to warn Britons that war could disrupt their food supply and somehow bring Britain to its knees. One wonders if urban designers in the early 20th century paid attention to his warnings.

The disruption of Syria’s food supply by civil war has been largely ignored by our media sources but nonetheless grave. While the media talks about casualties from weapons, little is said about deaths caused by famine and poison through the food systems in countries now at war. Few are aware of the destruction of livestock and cropland and the contamination of soil and water over the long duration of some of the modern conflicts.

The ripple effect of unrelenting conflicts is difficult to imagine. The most obvious effect is the breakdown of the infrastructure, especially the transportation of food. In Syria, even the perception of a disruption in the delivery of food causes an increase in black market activity, rising food prices, and higher incidences of hoarding. Pita bread, animal fat, and potatoes quickly disappear into basements and closets. More Syrians freeze and dry food for longer-term storage. As it becomes more and more difficult to transport food to Syria, Syrians look for more localized food sources. Commodities like fuel and flour begin to disappear, creating fears about being able to produce even the simplest but even more essential elements of their diet, flat bread. And, with the potential breakdown of Syrian’s government, comes the loss of state control of bread prices and ingredient supplies.

American cities see the connection between disruptions and urban food supplies mostly caused by natural disasters. New Orleans and New York City are keenly aware of the fragility of food supply chains when a natural disaster such as a hurricane destroys bridges and other food transport networks. In Manhattan, Hurricane Sandy’s impact upon fuel supplies alone immobilized food deliveries.

Cities today are routinely talking about three to five day food supplies, not the luxurious three month supply that Marston was angling for. Whether or not a city needs three days or three months … or three years is a question that needs more attention. Syrians are happy to have three minutes to consume a chemically free meal.

New York wants more than three days of food to keep it afloat in the future. Twelve months would be nice. But who’s to decide and how do we accomplish what Marston argued for in 1897, at least enough food for a country to adapt and find new sources of sustenance?