During a recent visit with a meat processor and a pig farmer in Argentina , I heard two men tell me stories that were disarming. Their stories seemed more suited to pass between intimate friends and unlikely to pass between us, having only met for a few hours. The stories, while they revealed how chorizo is made, were far more eloquent about their lives than about sausage or animal husbandry.

While we’re exploring the food supply chain, we’re often confronting machines, technology, the gears of the equipment that moves boxes from one place to another. These gears matter, but do the soft parts of the system’s underbelly, the human beings that make the thing work. Like the humans that work at Frigorifico San Jose on Darwin Street, on the fringes of Buenos Aires. In one moment, you watch a large meat grinder mince and mix meat for the sausage stuffers. In the next moment, you watch your host’s eyes brim with tears.

Ruben works at the pork processing plant housed in two buildings located in Lomas del Mirador. A rancher named Pablo Pelluse bought the land, where meat processors set up their businesses, in 1868. During the Argentinian Civil Wars, the area was caught in the regional battle and became known for its support of the Federalists fought against the Unitarios in Buenos Aires who wanted a strong, centralized government of the area. By the end of the century, the Federalists lost and Buenos Aires governed the unified areas around the city.

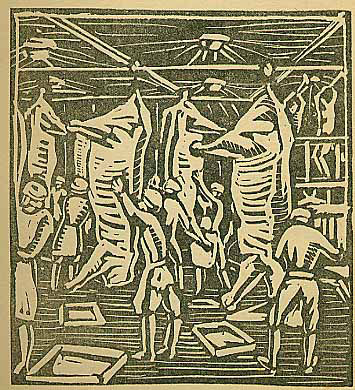

Aldolfo Bellocq, “Meat Packers, ” 1920s

Lomas del Mirador’s history runs along the same grain as the meat business in Buenos Aires. By the end of the nineteenth century, meat slaughtering had left its mark on the area as railways moved meat processing further away from the city. The meat processing companies that had existed in the area replaced slaughterhouses and tallow factories and provided employment to the surge of immigrants coming to live in Buenos Aires province during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, many from Italy. A soap factory, Jabon Federal, scooped up tallow to make bars of soap, joining other meat-related businesses and contributing to the appearance of other cities now known for its close association with the meat packing industry. A Chicago of the Argentinian meat industry, Villa Madero, like Lomas del Mirador, are historical artifacts of the old meat supply chain. The pork processing plant that I visited is one of the vestiges of the old meat processing neighborhoods of Buenos Aires.

Immigrants continue to occupy the area. Mario Klichinovich is the Product Manager and Ruben’s boss. Klichinovich is one family name you won’t find in Italy, but indications are that Mario’s family may have come from Austria but originally came as part of the Jewish diaspora from Russia. During the early 1900s, Russian Jews arrived in Argentina.

Ruben is a food scientist by training and has spent twenty-five years working in the meatpacking business. He began working in food service through an internship when studying food “engineering,” the term used instead of food “science” in the U. S.

He led us to the chilled meat processing rooms to find a line of table piled high with pig carcasses, mostly already cut into quarters and medium cuts. Workers hefted pig carcasses off the meat hooks inside a small truck that had been backed into the processing room. Occasional grunts revealed that this move took quite some physical effort.

Ruben’s team slices up a very small portion of Argentina’s pork production. Pig farmers have been increasing output by over 100 percent during the last decade, chasing a 60% increase in pork consumption. Exports of pork are also on the rise, in spite of Kirschner’s attempts to keep pork in Argentina.

Ruben’s company will need more space. His workers are bumping bags of pork, ham hocks, trotters against each other, flashing sharp knives, and tossing offal into buckets beneath the tables. The working space is clean, constantly rinsed by water and cleaning fluids, but at some point Ruben will need more cutting tables and meat processors to deal with what appears to be an increasing taste for Argentinian pork. Cheek to jowl, there’s no room to move without jostling the man cutting next to you.

After watching the ad hoc choreography required to empty the small truck and prepare meat for processing, we wandered upstairs where the sausage takes shape. Workers in pristine whites, boots and hairnets, swung into action, taking trays of cut up pork meat and sliding it into the jowls of the steel meat grinder. From out of a room containing buckets of spices comes the seasonings that will be mixed into the ground pork, including carmine, a natural red coloring for some of the popular red sausages. Carmine comes from the same bugs used to make cochineal, the deep red natural dye that we used on our farm to make organic dye for our sheep wool. One worker pours in the spices and dye, mixing the meat with a large shovel.

Steel tubs of ground pork become seasoned chorizo, some batches red, others not. Meanwhile, on another stainless steel bench, workers slip the end of a pig intestine onto a sausage filler. (I’ve tried to make sausage at home without one of these machines and it’s a Laurel and Hardy experience however long you work at it.) A sausage stuffer opens the sausage casing, made in the case out of pig intestines, to enable the sausage meat to fill the tube created by the intestine.

Ruben’s workers were slipping the stuffer into casing with lightening speed, inching up the casing while extruding pork mean into the tube as the next worker spun of lengths of string, tying the filled casing in increments of 6-7 inches. No doubt, this skill took hours of practice. Imagine the mistakes during the training period: sausages half tied-off, flinging loose sausage meat across the room. Ruben set up a small “sausage school” in the corner for novices to try their hands and filling and tying off meters of sausage before qualifying for the big table in the center of the room.

Back down in the cutting room, we saw the process begin over again. Moving into his office, Ruben explained that he needed to make a few calls to chase down payments and orders before driving us out into the countryside to visit one of his pig farmers. Along one counter, colorful plastic binders, spoke of Ruben’s attempt to bring order to the chaos in the next room.

In the car during the three-hour drive to the pig producer, I got a chance to know Ruben outside of his meat processor demeanor. I asked about his family.

He replied, “It’s a sad story.” His eyes filled with tears, as he drove on the highway, as he recounted how his wife passed away a week after giving birth to his two-year old daughter. His job, he confessed, was the only thing that held him together, providing one place in his life that remained unchanged, oblivious to the tumult he was feeling with his own life.

Without warning, we were talking about his deep loss, about his love for his daughter, about his fears for her future, his insecurities as her only provider.

Who are these people, working the pork processing supply chain? Working the loading dock, counting cases on a pallet? People like Ruben.

“Who are these people, working the pork processing supply chain? Working the loading dock, counting cases on a pallet?” This is a question I also often wonder. Are they all people with stories as sad as Reuben’s? Surely not. But I do call into question what keeps these people at these jobs, other than the security; the fact it is “the one place… oblivious to the tumult” they may be feeling in their lives.