If you want a new experience while visiting an art museum, try going as a food logistics nerd. Watch the docents and visitor services personnel freeze for a moment as they try to comprehend your request for guidance on finding all the art in the museum that represents different aspects of the food supply chain and food logistics.

Recently, I had this pleasure at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, the home of such luminaries as John Singleton Copley and John Singer Sargent. The two ladies at the front desk, each sporting particularly colorful eye glasses, one in flamingo pink and the other in cerulean blue, slowly warmed up to my request and began sketching a path through the museum on the printed floor plan. “Go to the Americas room and look for jars, and the Classical Art rooms and see if you can find amphorae,” they offered, visibly surprised that they had discovered something. For my part, I wanted to hunt down Winslow Homer’s images of fishermen lugging halibut.

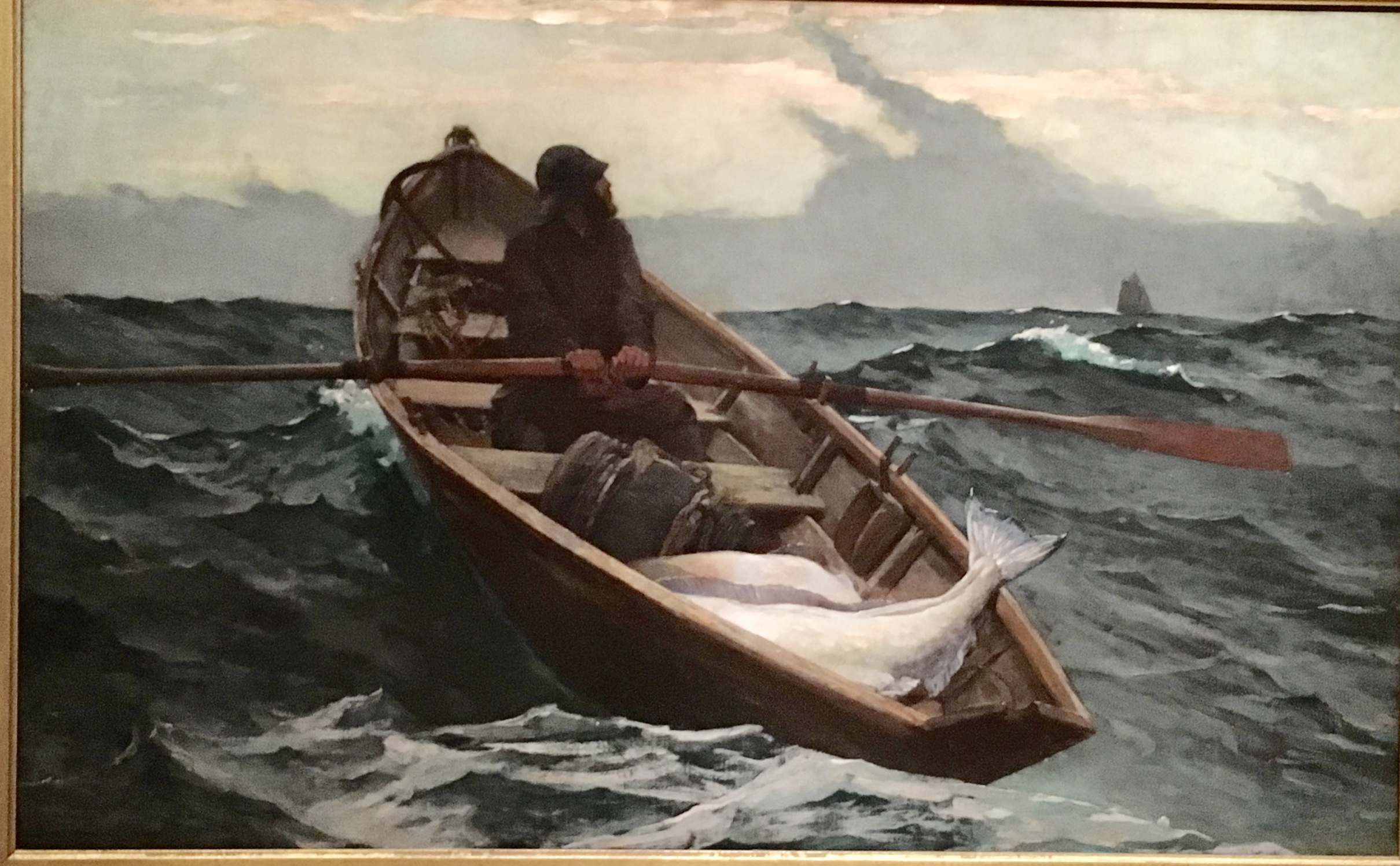

Here’s what I found. Winslow Homer’s The Fog Warning, the dark, foreboding image of a solitary fisherman, looking over his shoulder at the oncoming fog bank, his boat weighted down in the stern with two huge halibut. Did he make it home? There’s a schooner on the horizon in the distance. Did he reach them? Or know the ship? His boat is a fishing dory, a flat-bottom rowboat that was designed to carry large loads of fish caught at sea.

Winslow Homer

Fitz Henry Lane, an American painter known for his ethereal use of light, lived in Gloucestershire, Massachusetts where images of ships and the fishing industry surrounded him. Salem Harbor, painted in 1853, was the center of the China trade that brought not only silks but also tea from half way around the world. Square-rigged schooners and other working boats fill the harbor, unloading cargo into the Salem warehouses.

You can feel the chill of the Arctic wind in William Bradford’s Whaler in the Ice, Chopping Out. The black and white charcoal image illustrates the slow, cold journey taken by whalers hunting for spermaceti and other whale oil to fuel American households and their cooking stoves.

Whaler in the Ice, Chopping Out

Albert Bierstadt, the master of romantic, heroic American landscapes, recorded the demise of the ship Ancon stranded on a ledge in Alaska with its cargo of canned salmon. This 1869 oil painting, The Wreck of the Ancon, Loring Bay, captures the fragility of 19th century food logistics with ship’s cargo at risk of weather, ledges, and pirates.

The Wreck of the Ancon, Loring Bay

The rooms filled with Greek antiquities included numerous jars and amphorae that held food, water, and wine for various purposes, some for rituals, others purely utilitarian. One two-handled amphora from the Archaic Period (540-520 BC) gleamed from one case, displaying figures and grapes all the way around its midsection. As with most Greek vessels, the surface tells an elaborate tale of gods and humans. On this amphora, you see Dionysus (the Greek god of the grape harvest and winemaking) drinking wine while satyrs make wine. The process of winemaking graces the amphora, illustrating the various steps between the vine and your plate. Other, less ornate amphorae transported oil and wine across the Mediterranean in ships’ holds.

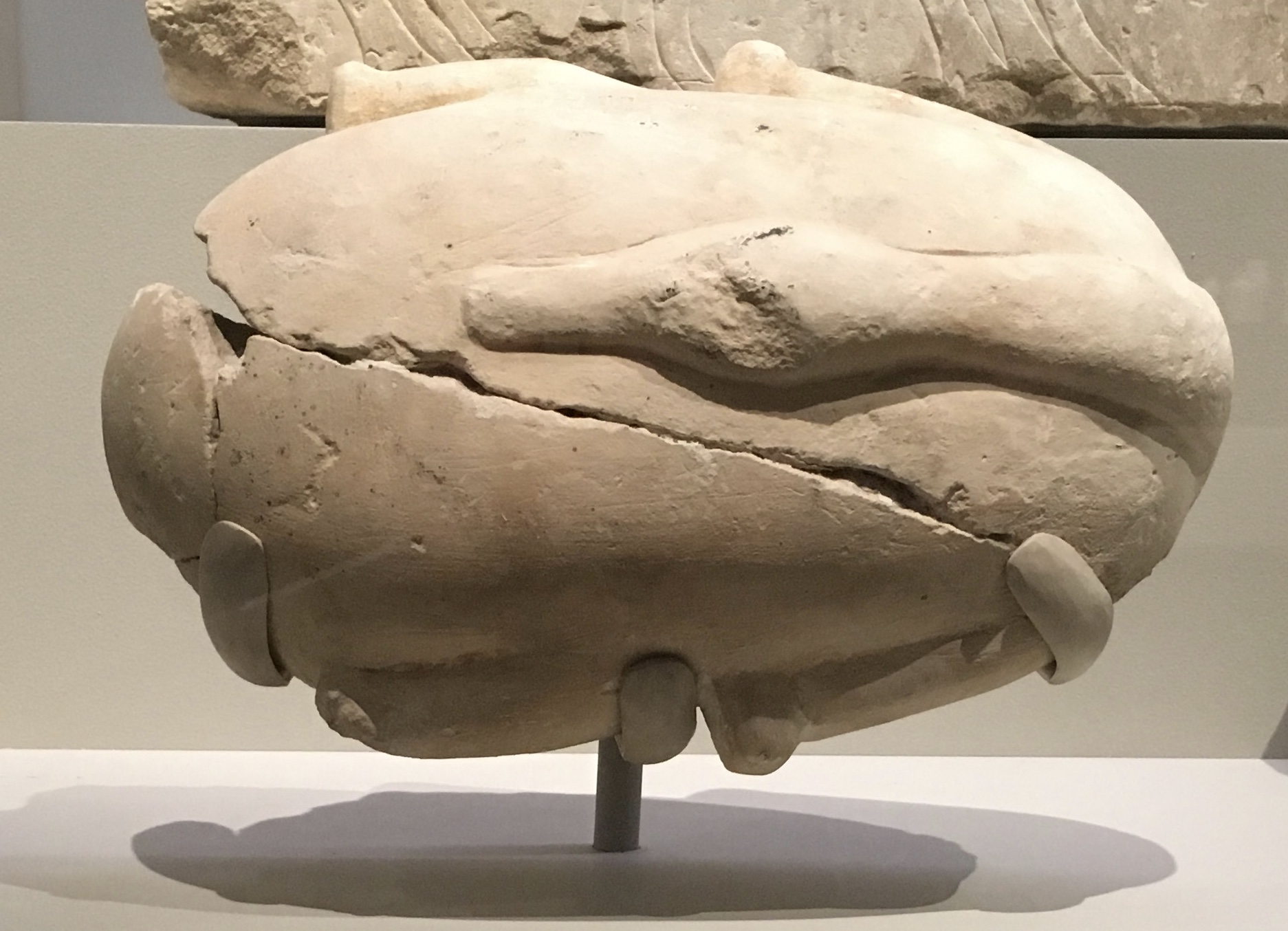

And finally, food transported to the dead is a food supply chain familiar to cultures that believe in an afterlife. The Egyptians assembled elaborate kits for those who departed from their world to the next. These stone containers, often depicting the food encapsulated within, contained the necessary sustenance to survive the next world. Called “food cases”, they were filled with provisions such as beef ribs and bread, sometimes wrapped in the same materials as the individual embalmed inside a sarcophagus. Notice this one has a duck carved on the exterior, suggested that a duck breast awaited the departed.

Imagining a museum as a repository of food logistics stories turned up some surprises and even more reminders that transporting food around the world has been going on at least since the Egyptians packed food for the afterlife. Whether in the next life or this life, the movement of food can be a combination of art and science, utility and aesthetics. Can’t wait to visit another museum with food logistics goggles.